From classical statues to the birth of cinema, medieval pilgrimages to public parks, and the first steps on the moon, walking has played a key role in Western art. This legacy includes Romantic nature-walkers, urban flâneurs, protest marchers, and modern cell-phone users. Artists like Van Gogh, Klee, Giacometti, Monet, Rockwell, Maya Lin, and Pope.L have all captured the act of walking (fig. 1). Evolving ways of walking have inspired new forms of artistic representation and shaped visual culture throughout history.1

My practice connects with artists like Bruce McLean, Francis Alÿs, Maya Lin, and Pope.L, who use movement as a key part of their work. McLean’s Taking a Line for a Walk (fig. 2) mirrors my own process, where walking and arm movements inform the marks I make on the canvas. Alÿs’s Green Line (fig. 3) and Lin’s Eleven Minute Line (fig. 4) reflect my interest in how the landscape influences my work. Pope.L’s crawling challenges traditional movement, which aligns with my embrace of provisionality and vulnerability in my art. Walking and physicality, are key to my process.

In examining these artists and their statements and work I have a clearer idea of studio intentions for next week at Demo, including techniques and processes for working on the floor.

Figure 2. Bruce McLean, Taking a Line for a Walk. Photograph, 1969/2011, 42.00 x 53.00 cm, Scottish National Gallery Of Modern Art.

Bruce McLean

In this piece, (fig. 2), and others from the same period, McLean prompts us to question what defines an artwork: is it the concept, the action, the photograph, or perhaps all of these elements? In this satirical image, he literally embodies Paul Klee’s famous assertion that "drawing is like taking a line for a walk." By doing so, McLean seeks to challenge the idolization of Klee’s teachings and subvert the myth of the ‘great artist.’ 2

Francis Alÿs

“Sometimes doing something poetic can become political and sometimes doing something political can become poetic” 3

In the summer of 1995, Alÿs performed a walk with a leaking can of blue paint in São Paulo, interpreted as a poetic gesture. In June 2004, he re-enacted that performance with a leaking can of green paint, tracing the 'Green Line' that runs through Jerusalem (fig. 3). He used 58 litres of green paint to cover 24 km. Soon after, he presented a filmed documentation of the walk to invited viewers, encouraging spontaneous reactions to the action and its context.

Figure 3. Francis Alÿs, The Green Line, Jerusalem, Israel, 2004; 17:41 min. In collaboration with Philippe Bellaiche, Rachel Leah Jones, and Julien Devaux.

Maya Lin

Lin’s Eleven Minute Line (fig. 4), is a large earthwork inspired by prehistoric burial mounds near her Ohio home. It blends a two-dimensional line drawing with a three-dimensional landscape, taking 11 minutes to walk its length. As visitors move along its path, their perspective shifts—uphill, downhill, or beside the sculpture—creating a dynamic interaction with the surroundings. The work changes with the seasons, encouraging viewers to reflect on the environment’s shifting nature.

Figure 4. Maya Lin, Eleven Minute Line, 2004, Sweden. Photos by Anders Norsell, Wanas Foundation.

William Kentridge

In his article for Freize magazine Tim Smith-Laing describes Kentridge as both dogged and prolific. Each powers the other in Kentridge’s characteristic technique of taking a line not for a walk but a think. 4

Although diverging somewhat from the initial ‘walking and not performing’ objective of mine, I felt it was important to examine other modes of interacting with public spaces and creating art through a mode of physical action. An example of this is American artist Pope.L.

Pope.L

In many of his performances he is crawling not walking, continually exploring spaces and forms that reflected his commitment to finding value in what he calls “have-not-ness.”5 Growing up in a working-class family marked by addiction and housing instability, he witnessed how precarious conditions could still foster creativity and imagination. This upbringing led him to believe that the “dynamic of pain, loss, joy, radicality, and possibility in the experience of being Black” represents a “lack worth having.”

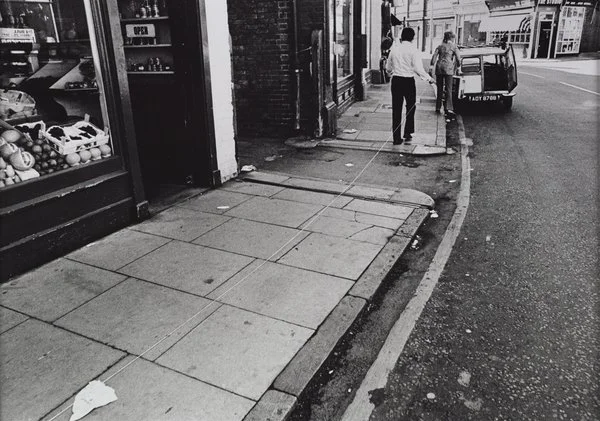

Crawling is a recurring gesture in Pope.L’s work, which he describes as “giving up verticality”—a way to become vulnerable for deeper understanding. Pope performs as his alter ego, Mr. Poots while crawling around dressed in a business suit with a yellow square sewn to the back, drawing curious stares from pedestrians (fig. 6). When a passerby asks what he is doing, Pope.L responds, “Working!”

This work, like many of Pope.L’s public interventions, engages passersby, whose reactions—whether engagement or indifference—highlight how social normalcy often relies on willful ignorance or disregard for certain bodies in public spaces.6

Figure 6. Pope.L, Times Square Crawl a.k.a. Meditation Square Pieces, New York, 1978, digital c-print on gold fibre silk paper, 25 × 39 cm.

Footnotes

1. William Chapman Sharpe, The Art of Walking: A History in 100 Images (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023).

2. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/125964, (accessed 29th Sept 2024).

3. William Kentridge, Video, "Five Themes": Taking a Line for a Walk, 2005, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3zTBXXXEbfw, (accessed September 29, 2024).

4. Tim Smith-Laing, "The Monumental World of William Kentridge," Exhibition Reviews, UK Reviews, October 19, 2022, https://www.frieze.com/article/william-kentridge-2022-review, (accessed September 29, 2024).

5. Ben Eastham, "Pope.L on Race, Power and Performance in the US," ArtReview, October 25, 2019, https://artreview.com/ar-october-2019-feature-popel/, (accessed September 29, 2024)

6. Eastham, "Pope.L," ArtReview, October 25, 2019.