Collage - Derived from the French verb coller, meaning “to glue,” collage refers to both the technique and the resulting work of art in which fragments of paper and other materials are arranged and glued or otherwise affixed to a supporting surface. It is useful to look at artists who employ collage as a central part of their visual-art practice.

Thomas Hirschorn's approach, (fig 1), as he describes it to us, is

"to create a new world in the existing world, to glue together what does not stick together. In order to do a collage, I need to act without my head, with courage, in pure affirmation, and with the instinct to make a break-through." 1

Thomas Hirschhorn. I-nfluencer-Poster (#Collage), 2021. Picture credit: Courtesy the artist, Alfonso Artiaco Gallery, Naples and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Photo: Grafiluce

This month I am exploring collage as a way to manipulate form and space by assembling a variety of materials onto surfaces. Collage introduces texture, depth, and dimension, allowing me to express different ideas while exploring spatial and emotional relationships through the arrangement of elements. Furthermore, collage constantly “surprises and subverts, pushing boundaries while embodying both power and poetry."2

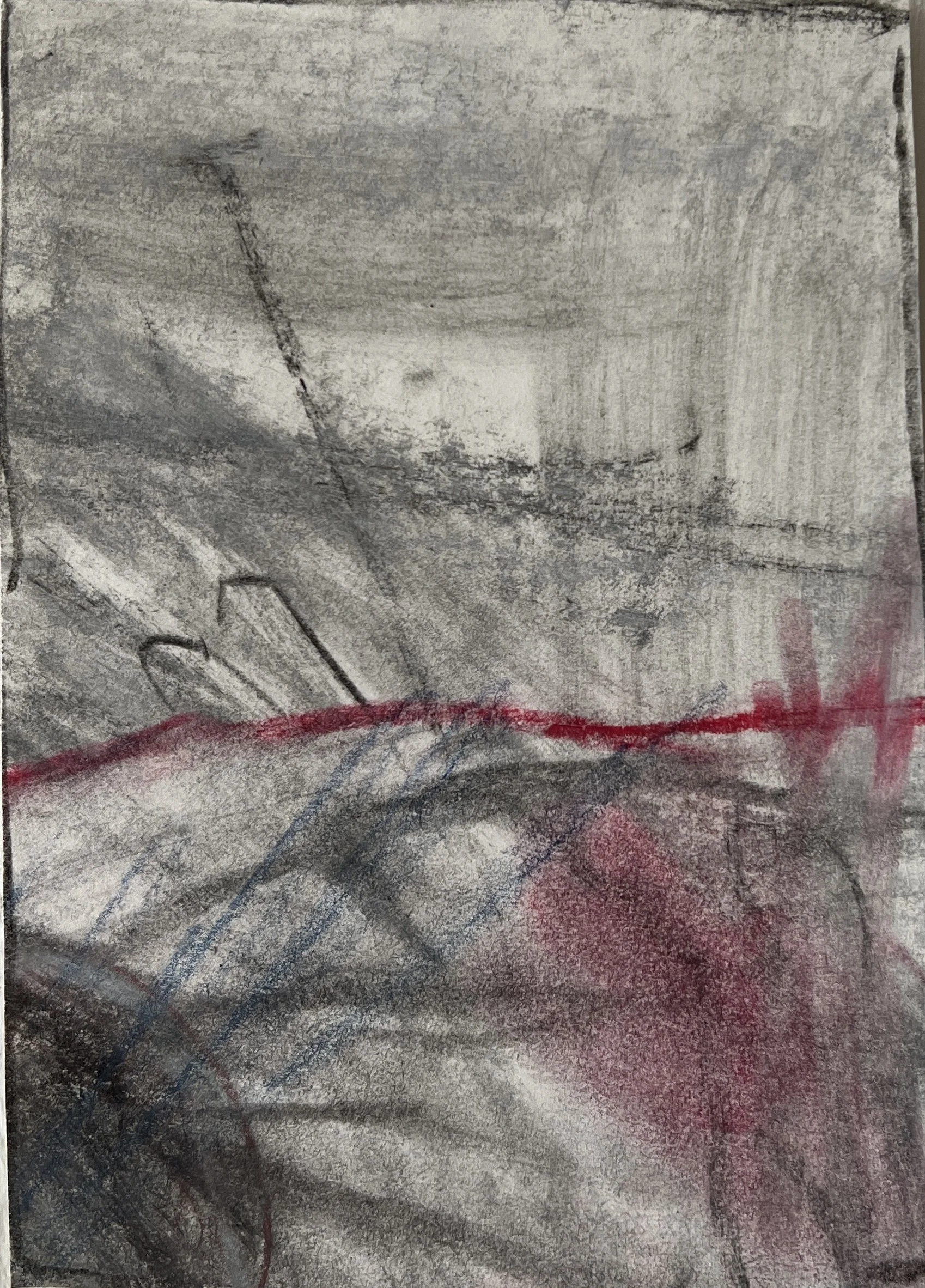

By using my own past work as the raw material to collage, I explore the self conscious, self generating processes to make new work.

I have seen a development in my work through the use of collage, the composition becoming a structural artefact that builds on itself rhythmically with line, colour, and form.

Two of my biggest questions or rather doubts I face in my practice is subject matter and composition.

postcards from the edge

2024

acrylic on cardboard and paper

I have tried to use collage as an enquiry into these concepts, and will use the constructs of process and materials to explore both. I have found in my literature reviews the ideas of ‘unfreedom’ and ‘emergence’ are 2 concepts that can be made to service the work. Unfreedom meant I set myself boundaries and rules to be able to create more quickly, (for example, using only my own work to collage from, setting up a premixed palette and determining the size of support used etc, imposing themes and time limits), and by emergence I mean responding to the work as it emerges, the artworks have unexpected qualities or meanings because of how they're made. This is especially clear to me in collage, when the joining of disparate elements create a fractured sense of composition that forms a new wholeness. The subject matter is the work itself and becomes its own subdividing organism. I began making more and more of these smaller works that seemed to feed off each other and create more possibilities than they shut down.

I am conscious of the idea that the “artist must grapple with conditions of uncertainty to construct visual meaning that is not pre-determined but “in-the- making” 3

Postcards from the edge 1-50

oil and ink on card and canvas

My work - Group Crit 1 summary

The main points to take away are as follows:

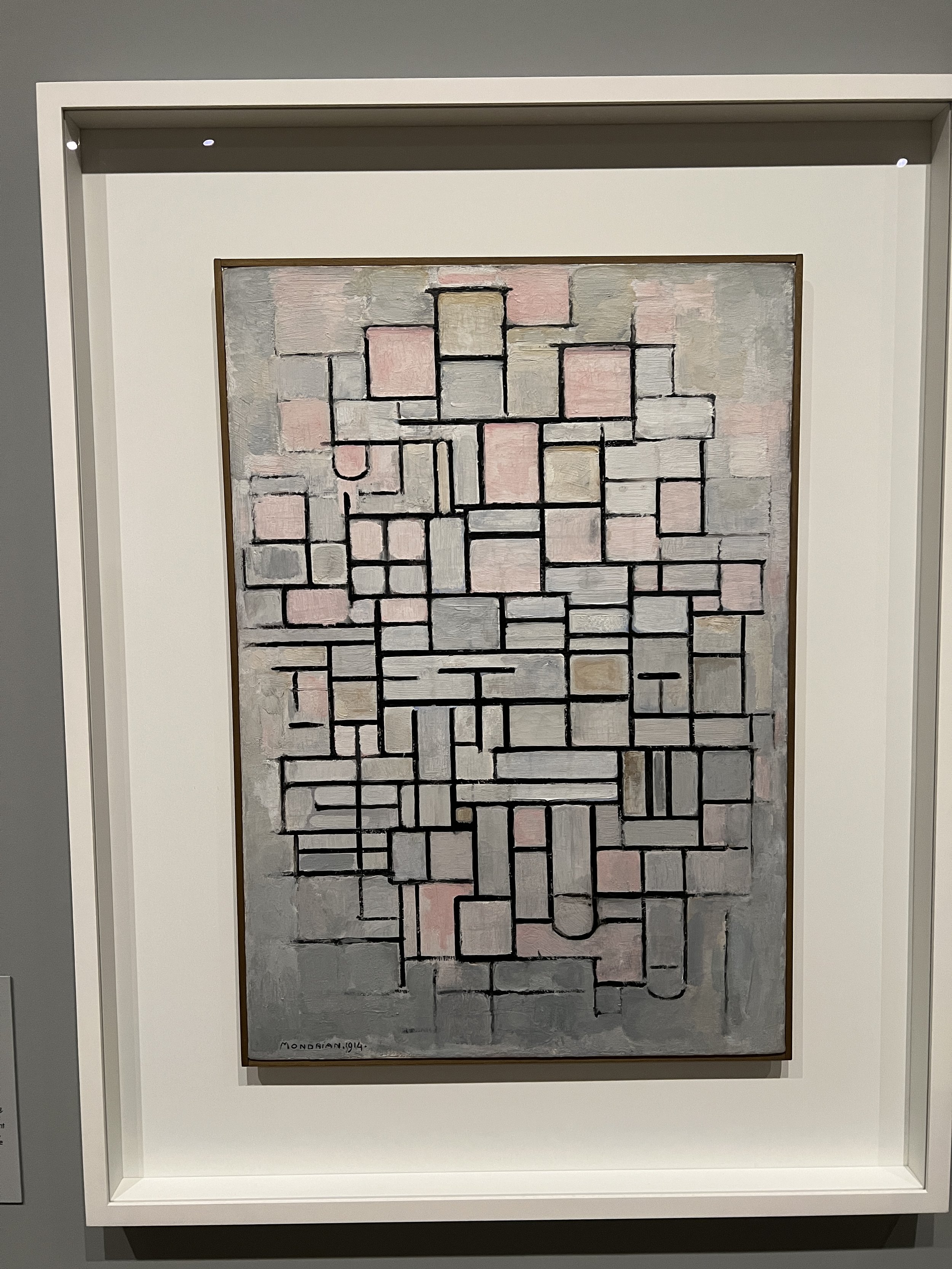

Abstraction and collage techniques are utilised, incorporating various elements and colours. These often featured landscape with the emphasis on horizontal forms occuring.

There's a sense of evoking the outside world, with certain elements resembling constructed forms found in architecture or urban settings. The layering of different moments within the artwork creates a sensation akin to flipping through the pages of a notebook or sketchbook. The artist's intention appears to be centered around experimenting with form and color, starting with small sketches that may later evolve into larger collage paintings. There's something unique that happens in collage that creates a line that cannot be achieved through other means, and even a small isolated work can command attention.

Themes are emerging, with a focus on exploring the idea of being in another place. The layers are flattened, creating a grid-like structure, and there's a desire to move beyond the confines of the frame, yet cropping can still be important.

The artwork has a sense of travel and also of looking through a window, capturing fleeting glimpses that evoke feelings rather than memories. There's consideration for preparing more thoughtfully, with the artist envisioning a window-wall-dream. Perhaps this can be explored more literally?

There are references to Fauvism with the use of wild colours, as well as influences from artists like Diebenkorn. Some of them suggest a depth that goes beyond mere illusion and embraces optical flatness. While the images are mostly abstracted, there's an inclination to attribute form to representation with a search for familiar elements like the horizon. The vitality of the work stems from this hybrid space between abstraction and representation, echoing the approaches of other female abstractionists from the past 10-20 years.

Group Crit 2

Noel: Direct us to the approach you want us to take - this is your second crit did you want us to pay particular emphasis to anything?

Sally: Now I’ve had it up for a few days I see lots of groups of things happening and it would be good if people would speak about things that stood out for them within these groups.

I’ve been exploring the horizon and the picture plane, objects that appear within the space and the ‘idea’ of nature and how we view it .

These ‘postcards’ grew in importance to me. They were originally a tool for generating ideas for paintings but have become things in their own right.

I started the process by collaging into sketch books and old books as I wanted a source of images for myself.

Noel: Did they evolve into landscape?

Sally: Yes after a while I wanted them to be about landscape but not necessarily representational. However I noticed how it was impossible to avoid the horizon, (thereby suggesting representation), even if it was deliberately left out. Maybe we are hardwired to see horizontal line as horizon and vertical line as figure.

Manny: I noticed an ambiguity to the one with an undefined horizon. I think that the horizon isn’t a place, it's somewhere you can never get to…you can’t go there and be a part of it, you can only experience it from afar! The ‘prison’ we are in means we are impelled to organise things all the time.

Noel: You were talking earlier about it from an audience perspective but perhaps you didn’t ‘attend to all the children’ and in one work left the horizon out… However this can be useful, and allow it to be a more speculative space, somewhere the audience can enter, in a way which is kind of productive.

Me: Yes I want the work to be a space for the imagination, we are striving to reach a place and if we can’t get there then that’s poignant.

Other readings of the work

Manny: There’s a couple of pieces where there’s almost a spaceship quality at first you think nature but then you think supernatural?

Natasha: Space exploration, and some landscape and some have an urban look, they open more possibilities than they close.

Me: I need perhaps to choose one and just work from that!

Mike: I like the way that the smallest amount of colour can make a big impact, it pulls you in and it doesn’t take much.

Noel: I'm also noticing the structure of the painting, which sometimes seems to work from the inside out. The rectangle, typically a compositional framework we must adhere to, is broken with pieces projecting out. This approach allows the image-making process to have a generative impulse, spreading out and following its own instincts rather than being confined within the rectangle. Sometimes this departure from the rectangle's confines is overt, while other times it's subtler, like the curvature of a cut line or the overextension of a collage piece. This creates a sense of urgency and immediacy, where the need to conform to the rectangle's edge is not prioritized.

Me: My urge was to ‘punch hole’ a regimented shape imposed on all of them, Noel may like the other way but I can always counter him or indeed my own inclinations.

Kerin: Reminiscent of Rothko, but there’s a lot of 20th C art referencing in the work.

Sally: It is referencing but it is also not, as it becomes my own.

Mike: there’s so much variety here, that it’s an excellent way of seeing what works and what doesn’t. some colour combinations are more evocative and conjure different feelings, there’s a subtlety to the colour combinations

Henry: You began the critique by mentioning that after observing the work for several days, you started grouping them based on their subject matter. It seemed like you were focusing on the "whats" of the pieces—their subject matter. I'm curious to know what qualities you see in each group that you respond to the most. Some pieces feature subtle light interventions, while others have heavy layers. Some use limited color, while others are vibrant. The prominence of collage varies among them. So, if you had to make groupings, which ones do you prefer, and why?

Sally: I enjoyed forcing things to come together in collage, making things, structuring things, drawing with material as it were.

Noel: Making things in separate spaces? Get a layer of cutting up?

Me: New interventions with old work and working on top of that as well. Whether the horizon will still try and force its way out I don’t know, maybe it will be a part of the structure

Noel: and the point that Henry was pushing toward, are you finding that there are particular approaches to colour you’re straining towards or things like that?

Me: I have a tendency to over saturate colour, so I’m taking on board perhaps the less is more in some cases.

Noel: Are there any thing’s that Sally might be ignoring or perhaps overlooking?

Henry: remove all the ones except the ones that really do what you want to explore to plan your next stage, otherwise it could go anywhere. Dig out what that is…

If it’s large collage don’t sanitize it… still leave spaces and edge and gaps etc.

Summary

We discussed the emergence of thematic groupings in my recent work, particularly focusing on explorations of the horizon, picture plane, and the concept of nature. My "postcards" have evolved from mere idea generators into significant standalone pieces in my artistic process. Other participants shared their interpretations, noting ambiguity in undefined horizons and analyzing the structure of my paintings. We also discussed my colour choices and collage techniques, with suggestions to refine my approach.

Footnotes

https://www.phaidon.com/agenda/art/2023/May/05/thomas-hirschhorn-why-i-make-collage/

Dennis Busch and Robert Klanten, eds., The Age of Collage Vol. 2: Contemporary Collage in Modern Art (Gestalten, 2016),

Jessica Whitelaw, "Collage Praxis: What Collage Can Teach Us about Teaching and Knowledge Generation," Journal of Language and Literacy Education 17, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 7. Ellsworth, (2005).