https://whitecliffecollege-my.sharepoint.com/:p:/r/personal/20230841_mywhitecliffe_com/Documents/Oral%20Presentation%20Part%203%20MFA.pptx?d=w4c2e50c65fc3470ca1b9e299d8b91181&csf=1&web=1&e=jxPCBm

Oral Presentation

The Impossibility of Painting

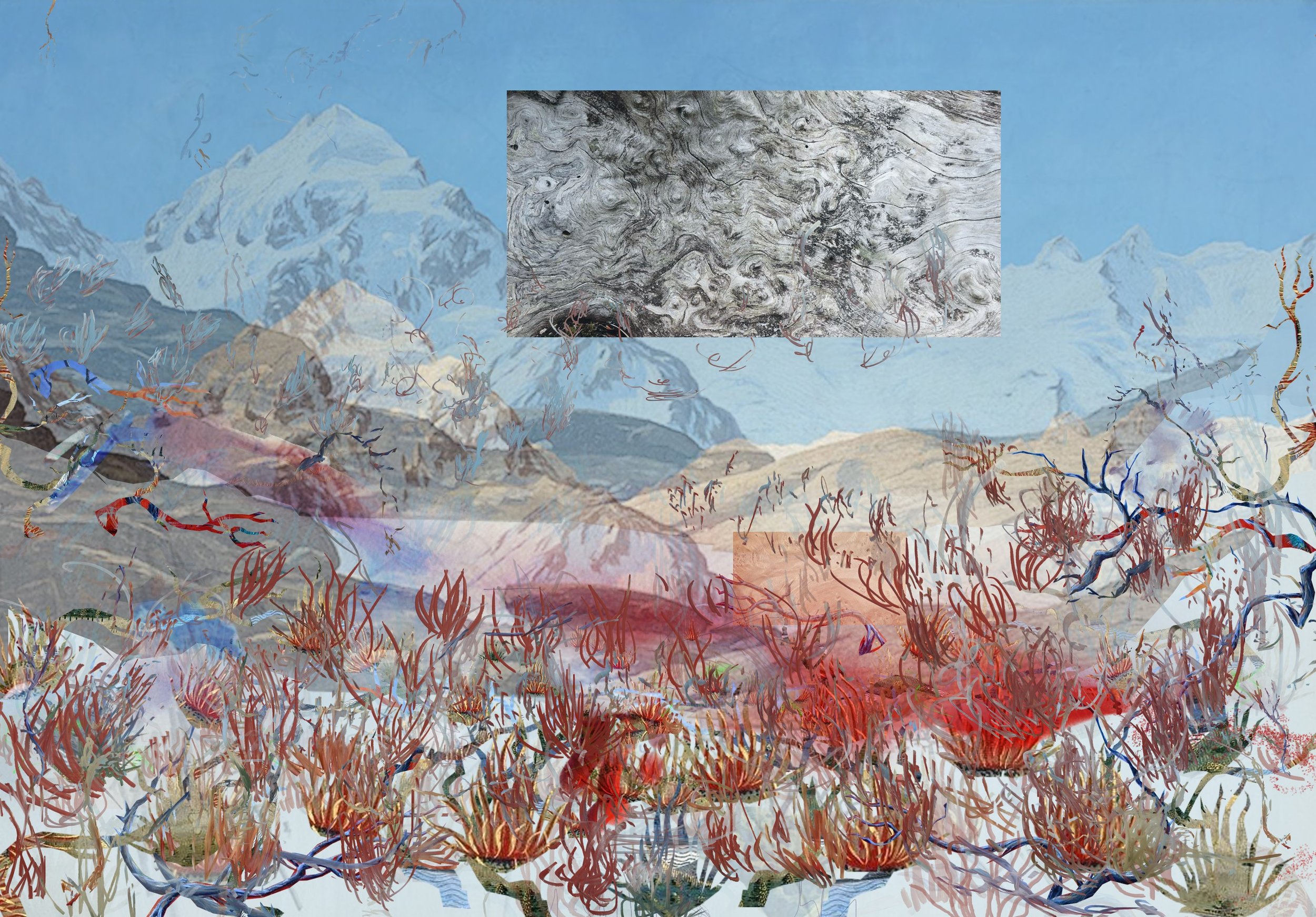

The tension that drives my work is living with the impossibility of finishing a painting. In my attempts to resolve this I have found three concepts to be helpful: membranism, emergence and provisionality. The central construct around which I situate these concepts is the daily walk to and from my studio. The walk taken as process allows me to position my body of work in Abstract art today.

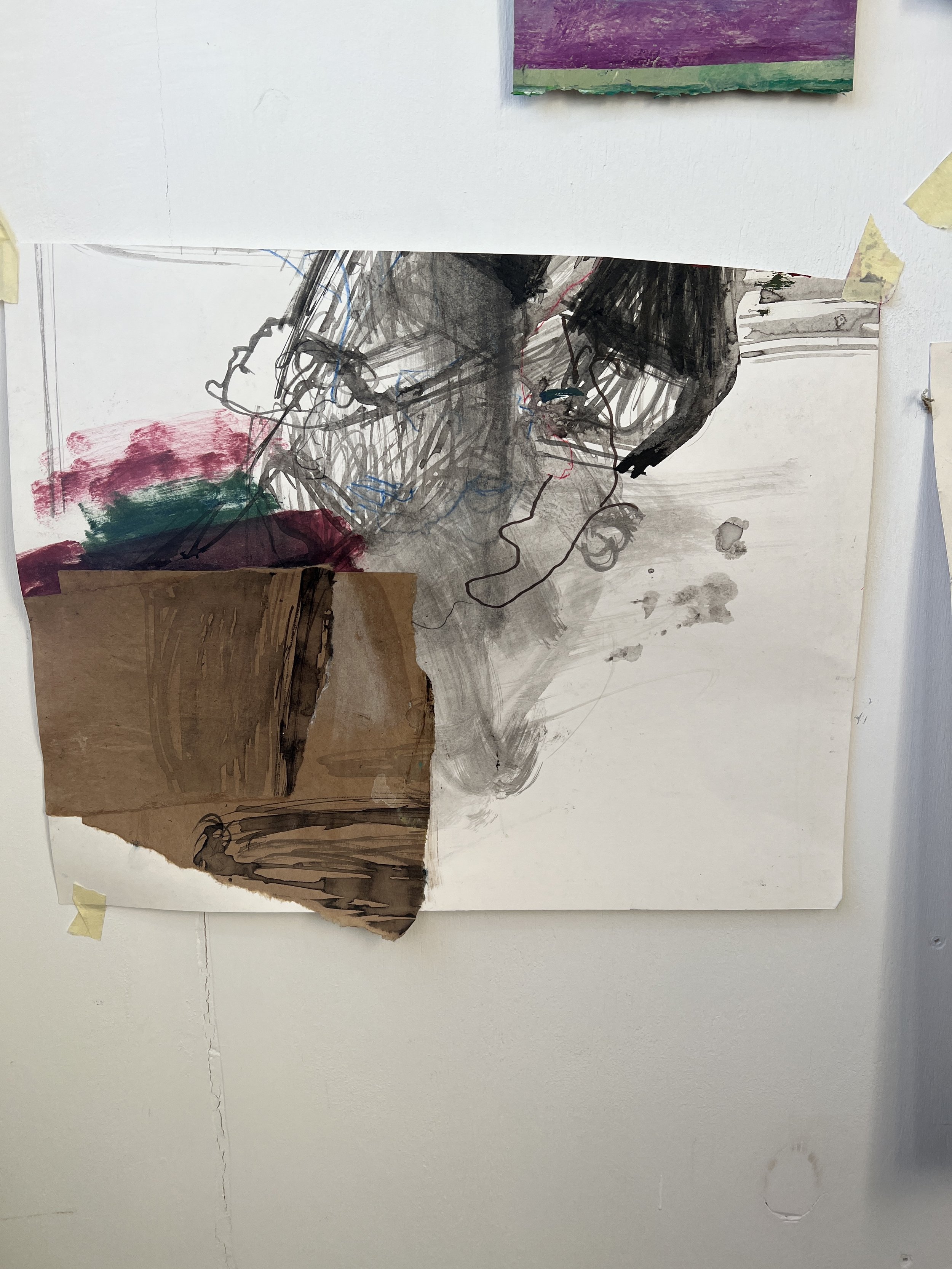

My practice embraces the challenge of creating paintings largely without planning, allowing each piece to evolve organically. By welcoming the potential for failure, these works represent cumulative attempts to realise form, leading to intermittent or iterative resolutions as they guide their own development. Drawing and collage are essential for generating ideas, incorporating diverse elements, embracing unpredictability and layering, and mirror the artwork's gradual emergence.

Talking the line for a walk

For me the urban walk offers a unique perspective on contemporary landscape painting. Every day I go from my home to the studio and back - a circular walk that begins and ends my day.

I explore the boundaries, edges and overlapping qualities between natural and artificial elements, finding inspiration in the contrast between park landscapes and urban surroundings like billboards and building facades.

Walking outside is the perfect antidote to what Virginia Woolf wrote of as “For there we sit surrounded by objects which perpetually express the oddity of our own temperaments and enforce the memories of our own experience..”[1]

I don't need to evaluate the process; it just needs to unfold.

Like the impossibility of declaring a painting finished, walking shows me that both painting and walking are open-ended acts, without a clear moment of completion.

While not the sole intention, these daily walks help me gather images. Furthermore moving on foot seems to make it easier to move in time; the mind wanders from plans to recollections to observations.[2]

If, as Paul Klee said, “Drawing is simply a line going for a walk,”[3] then my walk is like a ‘preparatory drawing.’

As I navigate the city, observing fleeting details and listening to both music and street noise, I engage in what can be termed “conscious languaging”[4] - a process where language overlays our sensory experiences, helping us craft cohesive narratives.[5]

This ability of humans to construct stories from observations, utilising pattern recognition and emotional responses, drives the continuous creation and depiction of our experiences.[6]

Walking naturally prompts me to piece together stories from my observations.

For instance, a blooming flower might evoke thoughts of changing seasons and personal memories, illustrating our inclination to link experiences to broader discourse. Recognising patterns—like anticipating rain from people carrying umbrellas—further aids in making sense of our surroundings. Sensations of light, form, and movement enrich this retelling.

My urban environment, with its ever-changing forms and ambient sounds, continuously informs my work.[7] I measure it against every place I’ve lived and the many thoughts I’ve had along the way.

This approach is a contemplative and personal way of creating, a synestheticprocess of absorbing both external and internal stimuli and translating them into the image. A process that can be explained in part by my first concept,

First Concept: Membranism

In her article "Membranism, Wet Gaps, Archipelago Poetics," Lisa Samuels argues that the Western paradigm of imagined order shifted from Time in the 19th century, to Space in the 20th, and finally to Contact in the 21st century.[8]Membranism emphasizes "wet" contact—an immediate, dynamic exchange between body and object, from the moisture of our fingers to the droplets of water in the air, this process flows from body to object, back to body, and then to a mental image, forming a three-dimensional, embodied, and active idea.[9]Membranism highlights the ongoing contact we experience, including the wetness of the eyes and brain as part of this interaction.[10]

Everything I perceive during a walk is mediated through this "wet" exchange. My paintings extend this idea of osmosis through wet-on-wet techniques, using oil, watercolour, glue, and ink on canvas and paper.

I am situated in Tāmaki Makaurau edged on many sides by water and find great affinity with Samuel’s term "Archipelago poetics"[11]. This refers to New Zealand and its unique relationship with the surrounding ocean, where islands are both confined and connected by the sea. It reflects the imaginative work that navigates uncertainty and unseen forces, challenging conventional notions of possession and control over the land.

Samuels speaks of “vibrant gaps”, positing the notion of the gap itself acting as a membrane through which sensation and knowledge can pass - of “ocean as fact and idea.”[12]

For me this mirrors the ‘gaps’ in seeing and perceiving and can be incorporated into my work, using my walk as an organising concept, and construct. In this way I view painting as an autobiographical act. The tensions in my touch and gestures when painting are influenced by my daily circumstances and contexts.

(I will note here that I have the sound of whales singing throughout the day from a city artwork outside my building– so the studio is permeable to external forces as well!).

My work reimagines and reorients a sense of locality, influenced by contemporary auto-fiction[13], stream-of-consciousness literature[14], and music, as I search for meaningful territories for myself.

Mental simulations also play a role in how I navigate my daily walk, from choosing the best route to avoiding crowds.

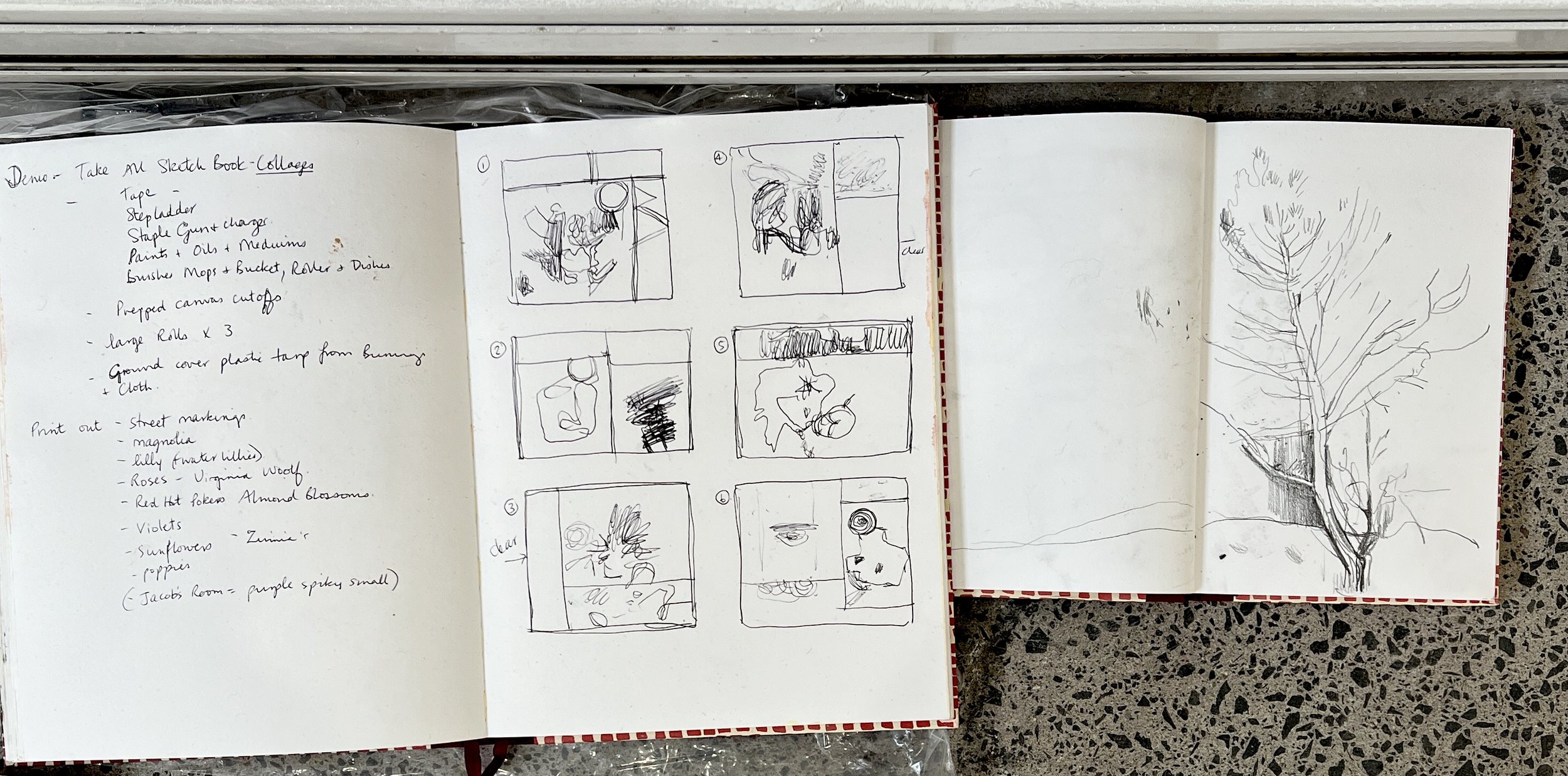

These predictions contribute to the ongoing description of my walks. Walking can be seen as a preliminary rehearsal—a period for organizing ideas, collecting impressions, and gathering images for potential use.[15]

This process is not systematic but involves integrating ideas with the surrounding environment. In the studio, I translate these observations into visual forms through collage and painting. Art emerges from this process.

Second concept: Emergence

Just as ideas and imagery emerge naturally during my walk, they also unfold in my painting through an extempore approach.

By this I mean I focus on intuitive art-making, where expanded consciousness, attention to specifics, and the fusion of artistic styles respond to light, shapes, and mood, aiming to evoke land rather than landscape.

Jan Verwoert's theory of 'emergence,' in relation to Tomma Abts' work, helps clarify the understanding of extempore painting methods. Verwoert describes how Abts' paintings evolve through a dynamic process where unpredictable elements interact and gradually shape the final outcome.[16] In this view a painting is not bound by a predetermined or fixed conclusion; rather, it emerges organically through the artist's continuous decisions and adjustments, with each stage influencing the next. [17]

This process aligns with André Breton's surrealist concepts of “the Encounter,” an unexpected discovery that captivates by chance, and “the Gesture,”[18] a more deliberate search for meaning. Together, these ideas reflect the surrealist belief in the interplay between chance and intention, a dynamic that has been integral to the development of abstraction, and that of emergence in paintings because it embodies the tension between the spontaneous and the deliberate.

In my own practice, the concept of emergence is also reflected in how walking influences my process, with different pathways or views shifting my perspective. Additionally En plein air painting and drawing alters my sense of pace, control, and distance, as light and weather impact the work. These outdoor experiences, once back in the studio, transform the external world into a remembered event.[19]

While I have spoken of the idea of conscious languaging during my walks, I intentionally avoid labelling or naming everything I observe. It is possible to describe without identifying. Language, and naming in particular, can never fully convey of our lived experience, which suggests the value of engaging with the world beyond the limits of words. This approach helps me avoid preconceived ideas and fosters a more direct and open interaction with my surroundings.

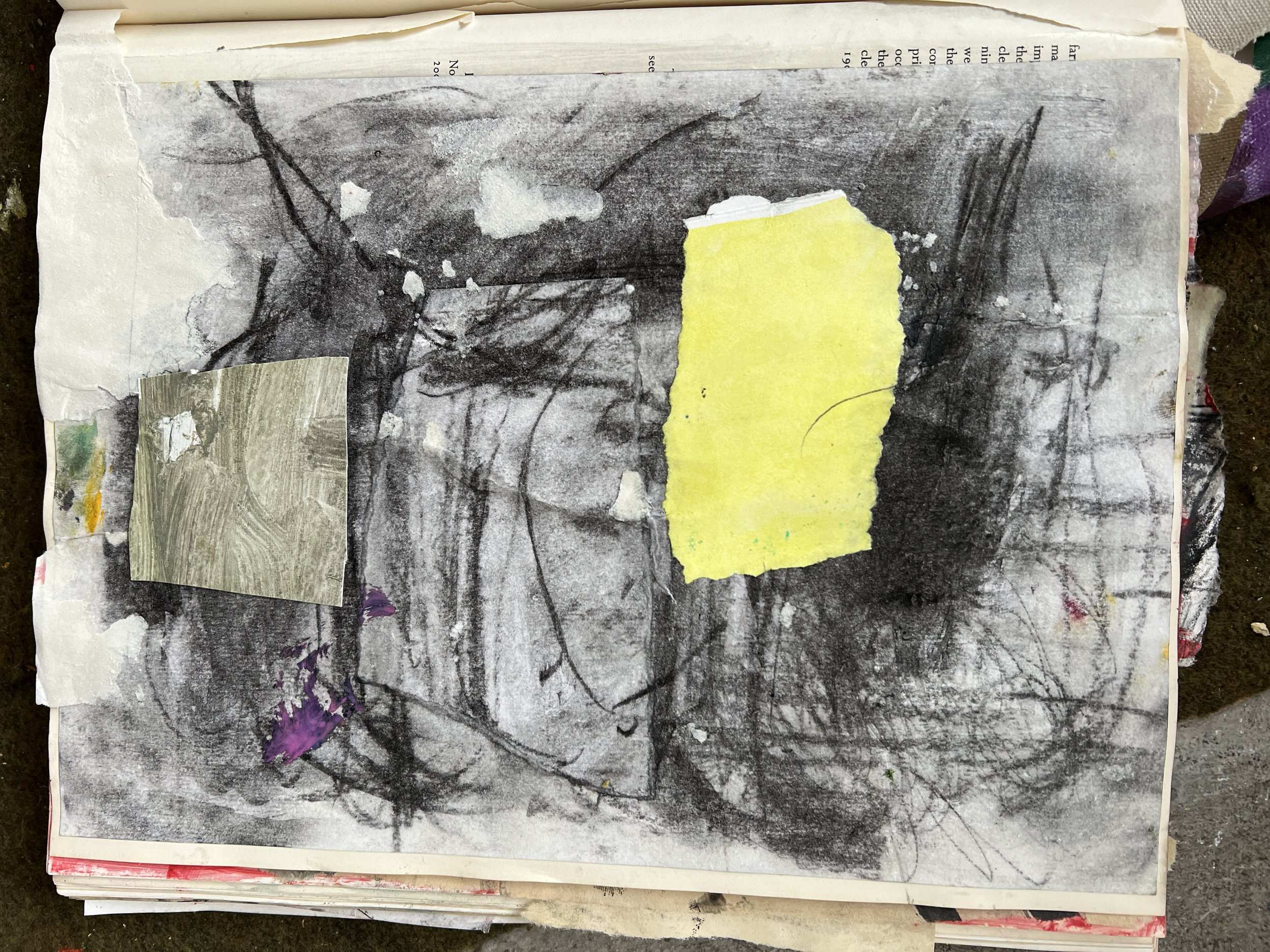

This process of openness to non-judgment also continues into the studio where I repurpose scraps and leftovers, which incorporates unexpected content into the work.

Constructing a wall of smaller postcard-sized collages, I acknowledged that the act of looking, of choosing and of making decisions was paramount.

I proceeded to scale up these ideas into an ‘Atlas’ of compositions using drawing and collage from past work, based on the landscape.

These in turn feed into my larger paintings. Each part of the process emerges from another.

What I see on pavements and in trees, as well as sensory details of colour, light, and sound are all visual information that can convey ideas. By focusing on abstract painting, I aim to suggest meaning through arrangement rather than definition. For me this process is assisted by collage.

Collage integrates the ideas of membranism and emergence by fostering a dynamic and fluid development that allows for continuous interaction, layering, and evolving meanings.

It is central to my work, engaging with notions of space, and memory. It combines Modernist principles with postmodernist elements like fragmentation, pastiche, and irony.

This approach reflects diverse perspectives, challenges fixed meanings, and aligns with postmodernism's focus on fluidity and ongoing dialogue. I consider it not merely as a technique, but as an action or a way of thinking.

By layering and collaging pictorial languages, I engage in a dialogue with artists across time.

While my approach to paintings and collages are formed by everyday life experiences, the focus remains within a realm of abstract painting, where I work within its conventions and possibilities.

The reasons I couldn't finish a painting seemed to echo the idea of the impossibility of painting, as it emerged through abstraction in the 21st century.

Abstract Art

My work is rooted in the established languages of abstract art, yet the term "abstract" originally meant to withdraw or separate. In art, it refers to works that either simplify or schematise objects, figures, or landscapes, or use forms like geometric shapes or gestural marks with no external visual source.

Associated with virtues such as order, simplicity, and spirituality, abstract art has been central to contemporary art since the early 1900s, when artists like Piet Mondrian seemed to point the way to “the abolition of painting as a craft”,[20] in so far as the skill of mimesis was no longer needed.

I explore the relevance of abstraction today by engaging with pre-modernism’s ideals of mastery and modernism’s focus on progress, while also questioning these concepts. My work emphasizes connection, hybridity and exchange, moving away from the alienation often associated with postmodernism.

This mirrors contemporary painting’s hybrid nature, blending styles like digital "cut and paste" to integrate drawing, narrative, and experimentation.

Western abstraction ranges from avant-garde's revolutionary ideas to formalism’s focus on medium. Today, abstract painting mixes these with personal explorations of memory, identity, and emotional responses.

This pluralism reflects the “Indiscipline” [21] of painting, a term coined by Rosalind Krauss describing how abstract art evolved from modernist traditions to a more experimental and hybrid approach.

An example of this is to be found in Art Historian David Ryan’s description of Fiona Rae’s paintings from the 1990’s as a “pick-and-mix”[22] look and a “patchwork of quotes” which resonates with my approach. Rae’s references touch on contemporary culture, they also engage with art history, especially American Abstract Expressionism, even if they don’t address it directly.[23]Rae reconfigures these references into a “developed collage,”[24], giving them fresh meaning and moving beyond simplistic appropriation, and ornamentation.

New Zealand artist Emma McIntyre extends this further. For McIntyre, ornamentation elevates painting from mere depiction to a dynamic stage of activity and imagination, where abstraction and figuration use gesture as both prop and performer, driven by a private narrative.[25]

There is an emerging cohort of other contemporary abstract woman painters who explore these same concerns, with an interest in pattern and ornamentation and an attraction to painting mainly defined by line.[26]

Pam Evelyn’s paintings, rich in texture, line, and colour, embody the concept of emergence by embracing uncertainty. Her works arise from the balance between intention and chance, rather than a fixed plan.

Evelyn’s use of eclectic tools and collage to explore disruptions in communication and perspective reflects a dynamic coexistence of references within contemporary painting.[27]

Like me, she uses techniques to encourage spontaneity, such as turning the canvas, setting it aside, and spending time observing rather than painting.

Phoebe Unwin explores both the physical and psychological realms, relying on memory and observation rather than photographs. She captures a subject by focusing on how colours interact with form, scale, and material tension. Unwin also embraces the unpredictability of her process, allowing memory to filter visual, emotional, and sensory impressions. She paints the feeling of an experience rather than its appearance, exploring what she calls, “languages of time.”[28]

Jadé Fadojutimi is known for her large-scale paintings, which she terms "emotional landscapes."[29]Although her work is mainly abstract, it often evokes natural forms. She explores themes of identity and self-knowledge by employing grids, layers, and varied marks to convey transformation and the interplay of colour, space, and mood.

I see how she treats the studio as a performative space for creation. By clearing away studio clutter and focusing on being present with my work, I allow the studio to become a space where paintings can evolve independently of the external world.

These ideas converge in the work of Los Angeles-based artist Sterling Ruby, whose collages blend found images, sketches, and gestural smears of pigment.

The philosophical notion of collage is central to Ruby's practice. He describes "illicit mergers,"[30] where the collision of different elements, ideas, and materials creates a visual mess—a hallmark of his style. His work's spontaneity and apparent randomness reflect a provisional approach, emphasizing the studio process, materiality, and transformation, ensuring that even scraps and cast-offs become opportunities for creative renewal, leaving nothing to waste.[31]

This brings me to my Final Concept: Provisionality

Key qualities of provisional methods include unpredictability, openness to change, and an embrace of impermanence. This action of countless revisions and revealed or hidden pedimenti, that prevent establishing any sense of finality, creates movement, a flickering in and out of resolution. If a painting is literally static its effects are not.[32]

These methods involve constant revision, a blend of familiar and strange forms, and a rejection of traditional notions of completeness or "strong" painting.[33]If an attribute of "strong" painting can be said to be that which is resolved, provisional works focus on process rather than resolution.

Art historian Raphael Rubinstein noted this trend in contemporary painting in the 2000s, seen in artists like Albert Oehlen, Mary Heilmann, and Michael Krebber, who favour a more casual, tentative, and unfinished approach, allowing for unexpected outcomes and fluidity in the creative process.[34]

These examples illustrate how contemporary artists grapple with the notion of "impossibility"[35] in painting.

This might stem from a sense of belatedness or a reluctance to engage with traditional expectations of greatness.

Painting that embraces impermanence and the unfinished, has its origins in artists like Giacometti, whose struggle to capture his artistic vision, as described by James Lord in A Giacometti Portrait (1965), involved weeks of reworking and self-doubt.[36]

Giacometti’s lament that painting is "impossible", underscored his belief in the unattainability of artistic goals.

This sentiment aligns with Sartre's concept of "negative work,"[37] where true artistic freedom is found in the ability to abandon a project at any moment. A nihilist approach or sentiment that seems to permeate all of society today.

“The collapse of traditional artistic forms and the rise of new media reflect a broader societal nihilism where the boundaries of reality and representation are increasingly blurred.” [38]

I would suggest that today's art isn't made for traditional ideals like truth or beauty, nor does it fully align with 'negative aesthetics' like Dada or 'bad painting.'

Perhaps as painter Amy Sillman suggests the key quality today is ‘awkwardness’ in art, reflecting a mix of control, discontent, and clumsiness.[39] She favours “metabolism” over “style”, describing it as a process where things change, become uncomfortable, and must be confronted, repaired, or risked.[40] In her paintings, each layer reveals the one beneath, with dissatisfaction and doubt integrating into the work’s substance. Rather than paralysing, doubt persists and contributes to the final composition. Sillman’s approach, therefore, transforms this standstill into an opportunity to introduce risks, culminating in a final state that, while uneasy, is her definition of resolved.

It is this persistence of doubt that becomes action in in my work, and by rejecting the idea of finality, of truly finishing a work, provisionality emerges as a vital aspect of my painting.

The concept of unfinished paintings is that which values incompleteness as a source of profound impact.[41] Unlike "last" paintings, which suggest a narrative of surpassing past works, provisional paintings may present preliminary works as finished.[42]

Provisional paintings can either reveal signs of struggle or appear effortless rejecting monumental, high-production art in favour of negation or lightness,[43] both of which resonate with a nihilistic perspective that finds meaning—or the lack thereof—in the process rather than the end result.

While some of my smaller works reflect simplicity and nonchalance, (an idea reminiscent of Matisse's appreciation of an ‘effortless’ style),[44] I mostly connect with the struggle and the 'unfinished' aspects of provisionalism.

Membranism, emergence, and provisionality all embrace movement, change, and incompleteness. They describe how boundaries are fluid, how complex outcomes arise from simple interactions, and how things are subject to continuous transformation. These concepts can also be applied to both walking and painting, reflecting how both activities involve ongoing adaptation and exploration, where nothing is fixed and everything is in a state of flux.

I often leave and return to paintings, labouring over them repeatedly. In this sense, my work could be considered provisional, as it involves self-cancelling actions - overlaying new paint, scraping back, adding, and reworking.

This kind of provisional painting acknowledges the potential obsolescence of painting while still valuing its possibilities. I work with the possibility of ‘abandonment’ while continuing to paint.

As Philp Guston reminded us, "Painting is impossible. Yet we continue to paint."[45]

Footnotes

[1] Virginia Woolf, "Street Haunting: A London Adventure," in The Death of the Moth and Other Essays (London: Hogarth Press, 1948)

[2] Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking (New York: Viking, 2000)

[3] Paul Klee, Notebooks: Volume 1: The Thinking Eye, edited by L. N. M. C., translated by H. W. W., (London: Faber and Faber, 1961), 53.

[4] Amanda Preston, "Artful Deception, Languaging, and Learning—The Brain on Seeing Itself," Open Journal of Philosophy 5, no. 7 (November 2015): 343–350, https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2015.57049, accessed August 4, 2024.

[5] Amanda Preston, "Artful Deception and the Brain," Open Journal of Philosophy 5, no. 7 (2015): 343–350.

[6] Preston, Artful Deception and the Brain

[7] Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, [1929] 1957), 51.

[8] Lisa Samuels, “Liquid State, Membranism, Wet Gaps, Archipelago Poetics”, Journal of Contemporary Poetics 10, no.2 (2024): 75-89

[9] Samuels, “Liquid State”, 75-89.

[10] Samuels, “Liquid State”, 160.

[11] Samuels, “Liquid State”, 160.

[12] Samuels, “Liquid State”, 160.

[13] Karl Ove Knausgaard, So Much Longing in So Little Space: The Art of Edvard Munch, trans. Ingvild Burkey (London: Harvill Secker, 2021)

[14] Virginia Woolf, The Waves (London: Hogarth Press, 1931)

[15] Francis Alÿs, As Long as I’m Walking, ed. Nicole Schweizer, with texts by Julia Bryan-Wilson, Luis Pérez-Oramas, and Judith Rodenbeck, (Geneva: Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts of Lausanne and JRP Editions, 2021), 160 p., 277 ill.

[16] Jan Verwoert, “Emergence: On the Painting of Tomma Abts,” trans. Hugh Rorrison, in Tomma Abts, ed. David Zwirner (Cologne and London: Galerie Daniel Buchholz and Greengrassi, 2005), 41–48.

[17] Verwoert, “Emergence,” 41–48.

[18] André Breton, Mad Love (New York: New Directions, 1961), 25–30.

[19] James Ambrose, "Pam Evelyn: A Conversation on Process and Painting," Emergent Magazine, 2023, https://www.emergentmag.com/interviews/pam-evelyn, accessed September 10, 2024.

[20] Russell Ferguson, The Undiscovered Country (Los Angeles: Hammer Museum, UCLA, 2004), 53.

[21] Daniel Sturgess, "The Disciplines of Indiscipline: Rosalind E. Krauss’s Legacy," Art Journal 75, no. 4 (Winter 2016): 15–25.

[22] Cordeiro, Conceição. “Times of ‘Cut and Paste’: A Hybrid Reading of Painting.” Journal of Contemporary Art Studies 5, no. 2 (2022): 45–60.

[23] Cordeiro, “Times of ‘Cut and Paste,’” 45–60.

[24] Cordeiro, “Times of ‘Cut and Paste,’” 45–60.

[25] Evangeline Riddiford Graham, "Emma McIntyre: Big Crafty Angels in the Garden," Art News, September 25, 2023, accessed February 10, 2024, https://artnews.co.nz/big-crafty-angels-in-the-garden-emma-mcintyre-spring-2023/.

[26] Sam Cornish, "The Reason for Painting," Studio International, June 6, 2023, review of The Reason for Painting, Mead Gallery, University of Warwick, May 4 – June 25, 2023, https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/the-reason-for-painting-review-mead-gallery-university-of-warwick.

[27] Ambrose, "Pam Evelyn: A Conversation on Process and Painting."

[28] Phoebe Unwin, Slow Movement (London: South London Gallery, 2021), exhibition catalogue.

[29] Habiba Hopson, "New Additions: Jadé Fadojutimi," Studio Magazine, April 5, 2023, https://www.studiomuseum.org/magazine/new-additions-jade-fadojutimi, accessed September 10, 2024.

[30] Scott Indrisek, “Making Sense of Sterling Ruby’s Beautifully Grotesque Art,” Art, November 1, 2019, 9:56 AM, accessed August 17, 2024, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-making-sense-sterling-rubys-beautifully-grotesque-art.

[31] Indrisek, “Sterling Ruby.”

[32] Russell Ferguson, The Undiscovered Country (Los Angeles: Hammer Museum, University of California, 2004).

[33] David Joselit, Art Since 1980: Charting the Contemporary (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2013), 45.

[34] Rubinstein, “Provisional Painting,” 53–59.

[35] Rubinstein, “Provisional Painting,” 53–59.

[36] James Lord, A Giacometti Portrait (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1965)

[37] Jean-Paul Sartre, "The Imagination and the Negative," in Existentialism and Human Emotions, trans. Bernard Frechtman (New York: Philosophical Library, 1957), 83–94.

[38] Paul Virilio, The Original Accident, trans. by Julie Rose (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007), 41:

[39] Amy Sillman, “Notes on Awkwardness,” in Amy Sillman: The Shape of Things to Come, ed. Laura Hoptman and Robert Storr (New York: The Drawing Centre, 2021)

[40] Amy Sillman, “Notes on Awkwardness”.

[41] Rubinstein, “Provisional Painting,” 53–59.

[42] Rubinstein, “Provisional Painting,” 53–59.

[43] Rubinstein, “Provisional Painting,” 53–59.

[44] Rubinstein, “Provisional Painting,” 53–59.

[45] Philip Guston, Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, ed. Kristine Stiles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 114.